I was waiting for the J train when I found out my husband was dead. I had left work earlier than usual, and the underground Embarcadero Muni Station, which was so jammed during rush hour that it was difficult to walk down the platforms, was nearly empty. My phone had only one bar of reception, and the ringing from my phone had startled me. The screen read “San Francisco, CA” below the unknown number.

“Mrs. Anderson?” said the voice on the phone.

“Yes?” I said, remembering the first person who’d called me that: the bellhop at the hotel where we stayed on our honeymoon, only a few months ago. I’d been startled when he spoke. Who? I wanted to say. Who is Mrs. Anderson?

When I had told Mable how upsetting it was for me to be called “Mrs. Anderson” a day after the wedding, she said, What did you expect when you changed your last name? You’ve erased yourself on two fronts. As a woman and as an Asian American woman.

The train whirred past me, and I was tempted to hang up. I was impatient to get on with what I felt the night should look like: getting on the Muni, walking to the bar that almost always smelled like ammonia, having drinks with Mable, which meant getting drunk or at least earning a respectable buzz, and then somehow making my way back home.

“Where are you? Are you sitting down?” the man asked, letting out a small cough between the questions.

“No,” I said. I had been listening to music when I picked up the call, the ringing interrupting the song, and now I pressed my headphones more firmly into my ears.

“Are you driving?”

“No. I’m sorry, who is this?”

“I’m afraid I have some bad news. Your husband was in a serious car accident. He’s dead.” He spoke clearly and firmly, as if underlining each word twice. He gave me his name and the name of the hospital he was calling from, one I recognized from its association with a medical school. On the other end of the line, I could hear him shuffling papers, and I imagined him as a young resident, likely trained to deliver news from some mnemonic device or protocol. He began to list the names of procedures (all intended to be life-saving, but all ultimately unsuccessful) and then repeated those words again, He’s dead. He repeated the name of the hospital and told me to come in as soon as I could. I said nothing, just hung up.

I found myself leaving the station. I could smell urine as I headed toward the stairwell to the exit, the daylight streaming ugly through the Muni street opening. A pigeon by my feet had curled up its left leg so it looked like it was dancing instead of limping. I dropped my phone at the top of the stairs and the screen shattered. “Sucks,” a teenage boy said as he passed. The back of his head was dyed pink.

The phone still worked somehow, though, and I requested an Uber to the hospital. A car was just around the corner, and I felt thankful when it arrived. It was a dirty Camry whose driver grunted at me as I buckled myself in. I wondered if Ian had been wearing a seat belt when he died. The car made a few turns on local roads and then turned onto a freeway on-ramp.

Even though Ian and I were young and barely married, I had already spent at least a handful of hours wondering what it would be like to receive this kind of news. This imagining usually happened as I was curled up next to him while he slept, a mound of comforter rising and falling like a metronome. I felt I’d first deny it, swear up and down that they had the wrong Mrs. Anderson. It couldn’t be him, I’d say, I just saw him this morning. There are a million people with this last name. And then, after I’d accepted my fate, been forced to after identifying a splotchy birthmark on his hip, I would start to plan the funeral. I ran through lists of our friends, deciding whom I’d ask to speak, who would send flowers instead of attending, and who would show up but eventually disappear from my life. The images that would go through my mind were clichéd, drawing from the scenes that Mable and I made fun of in movies and television shows.

But my imagined reaction was nothing like my real one. Even though I was gutted, sickened, wanted to hurl myself out of the back seat of the moving car or curl myself into something so small it no longer existed, I didn’t question the fact of it. Two words made me so certain: car accident. Ian had always driven like a maniac. When we first started dating, I’d pretended I found it frightening, gasping whenever he cut across four lanes of highway traffic to pull off at an exit, the sounds of car horns following us. But really, I loved it. I thought it made him different from the other lawyers I’d met, whose pleated khakis created unflattering mounds and lumps where they shouldn’t be.

From the Uber, I called my mother, who picked up after two and a half rings.

“Did you see Carol’s invites?” she asked. “I swear they used the exact same vellum we did.”

“He’s dead,” I said. The driver caught my eye in the rearview mirror.

“What? What did you say?”

I repeated myself three times, then told her I was already on the way to the hospital. Even though she was in Ohio, I gave her the hospital address, too. She started crying and shouting until I said, “I just got here, I have to go now.”

“I’m sorry,” said the driver as I hung up and exited his car. Inside, a main desk receptionist directed me to an elevator in which a man lay under a thick blanket on a gurney, his eyes closed. Next to the gurney stood a doctor in a white coat who was using his thumb to scroll through a social media app on his phone, only slowing down to study pictures of someone’s vacation. There were shots of a beach, a man holding a frosted cocktail. A woman with coral red lipstick, a parrot on her arm, was midscream when another photo was taken. It was supposed to be a playful picture, but it looked frightening to me. The man on the gurney whimpered and the doctor glanced down.

“Almost there,” he said.

On the Emergency Department floor I spoke to someone behind a desk. She typed his name into her computer and then looked up briefly at me and back down at her keyboard. She said, “Hold on, let me get someone for you.” I realized then that the news of his death might’ve been hours old when it reached me. He could’ve been dead when I was eating lunch, picking shrimp tails out of my salad and laying them in a spiral on my napkin. Or this afternoon, when I’d closed my door and pretended to be on a conference call but really just texted with Mable to make plans.

The woman got up from her desk and walked down the hallway. She wore a set of pink scrubs, and on her collar there was a pin of a smiling cartoon bear holding a bunch of multicolor balloons. I saw her speaking to a group of people wearing blue and teal scrubs. When she returned, she said, “It won’t be much longer.”

A man standing with the group of people she had just spoken to came up to me and introduced himself as the doctor who had called me. I said, “You look older than you sound.”

“Let me take you somewhere quieter,” he said.

He led me into a small room off of the waiting area, where he had me sit down on a small couch and took a seat opposite me. He explained that my husband had arrived at the hospital after suffering serious injuries from a car accident. He once more listed all the procedures they had done. There was nothing we could do, he kept saying. The entire time he was speaking I had to stop myself from leaning across the couch and shaking him, even striking him. It seemed appalling that he could say such words to me. Instead, I asked to see Ian’s body, and the man told me he’d take me to the morgue.

As I followed him out, my phone buzzed. My mother had texted that she’d be on the next plane out to San Francisco, and sent me her flight number. Mable had sent me a string of question marks, and I realized that I hadn’t canceled our drinks date. I imagined her sitting at our table at the bar, the one equidistant between the door and the bathroom, positioned so we wouldn’t catch the cold breeze outside or have to hear the toilet flushing. She still had the luxury of not knowing. She was still on the other side.

__________________________________

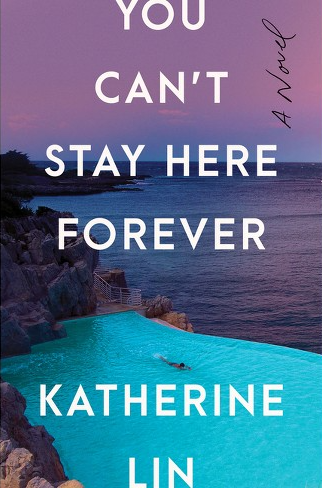

From the book You Can’t Stay Here Forever by Katherine Lin. Copyright © 2023 by Katherine Lin. Reprinted courtesy of Harper Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.